What is red light therapy?

In recent years, red light therapy, also known as phototherapy or light-emitting diode (LED) light therapy, has gained attention as a potential tool to enhance fertility in both men and women. This article will explore red light therapy and its impact on reproductive health. This includes who can benefit from it, the safety of red light therapy, and how it may potentially improve factors such as blood flow and cellular energy.

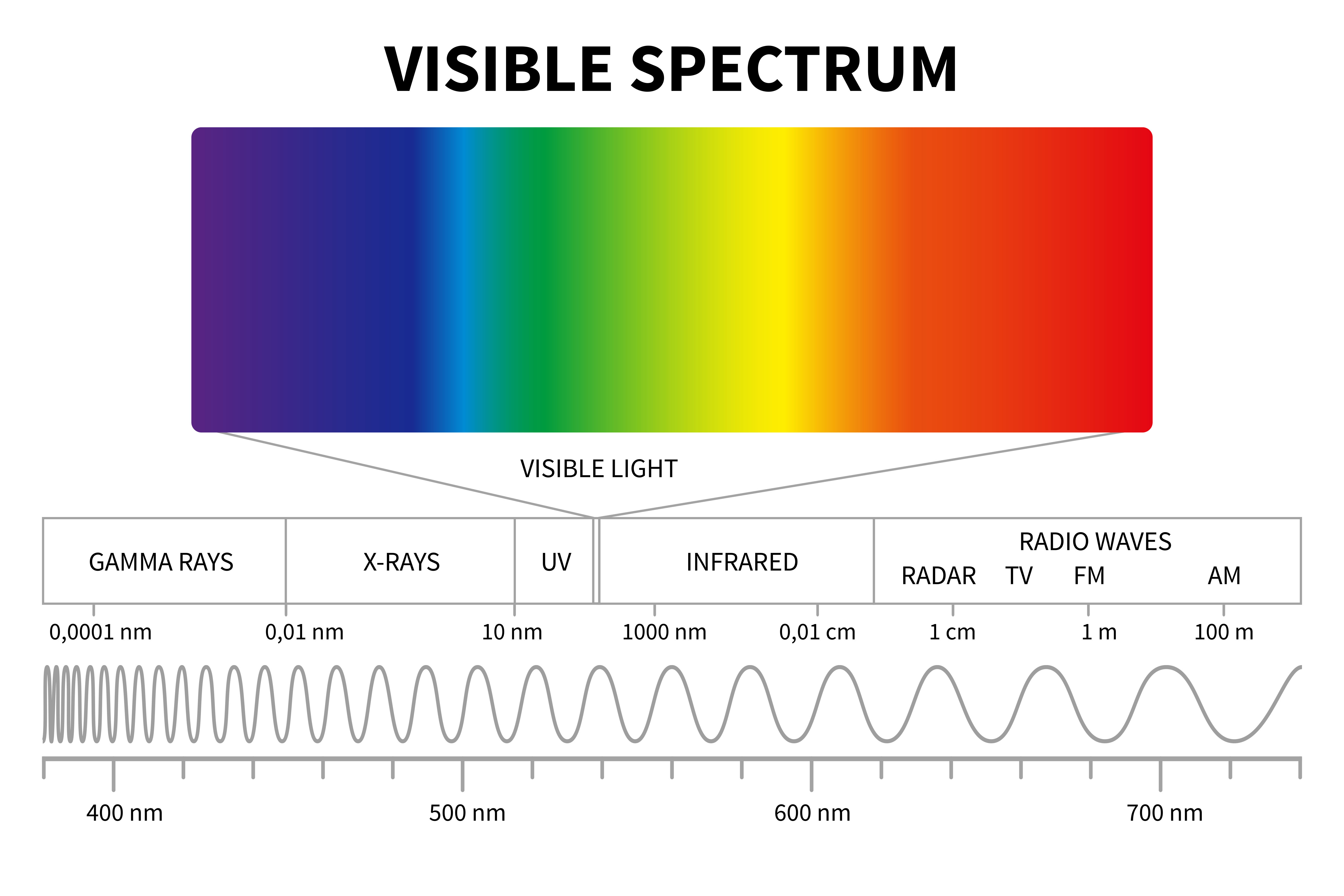

Red light, which has a wavelength between 620-750 nanometers (nm), contains energy that may become absorbed by target cells. Infrared light (750-1000nm) is also sometimes used in low light therapy, and even called red light therapy, despite it being in the infrared range. In comparison to other visible wavelengths, red light is better able to penetrate deeper tissues due to a longer wavelength.i Light with longer wavelengths has lower energy compared to light with shorter wavelengths. Red light therapy utilizes a type of light emitting diode (LED) light which emits a relatively low level of energy in comparison to non-visible light or UV lights.ii

Red light therapy is often referred to as low level light therapy (LLLT), low-level laser irradiation, or laser acupuncture. In addition, it is believed that exposure to red light is not associated with DNA damage, unlike UV light which is known to increase the occurrence of skin cancer.iii

There are a variety of proposed mechanisms as to how exactly red light therapy works, and the exact mechanism remains unclear.iv Exposure of human cells to certain light intensities has been shown to increase cellular processes, including cell proliferation (increase in cell number) and metabolism.v,viIt has been proposed that the energy emitted by red light triggers these beneficial cellular responses when the energy is absorbed by mitochondria,vii which are present in varying quantities in almost all cells. Mitochondria are cellular structures that produce energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is utilized by the cell.viii,ix

Red and near infrared light have been used clinically as a noninvasive therapy for many years in fields other than fertility, including dermatology, dentistry, and neurology. For example, it has been used to promote wound healing and treat chronic joint pain.x,xi It is believed that the benefits connected to red light therapy are based on improvements in blood flow and angiogenesis (creation of new blood vessels).xii, xiii This is believed to occur due to changes in a chemical compound called nitric oxide (NO), which is discussed below.xiv

Can red light therapy improve fertility outcomes?

As discussed, red light therapy has been shown to have certain clinical benefits in other fields, and research into red light therapy for fertility may one day support its clinical application. Photobiomodulation via red light therapy is believed to enhance mitochondrial energy production, particularly in stressed cells.xv This is relevant to eggs and sperm because they both require a high quantity of mitochondria for their functional needs. For example, the oocyte contains an extremely large number of mitochondria (100,000-100,000,000) compared to other types of cells,xvi which is necessary due to the large energy demands of oogenesis and later in embryonic development.xvii, xviii The sperm cell midpiece contains approximately 50-75 mitochondria, which is a high density for the small cellular area it occupies.xix

Mitochondria from sperm do not become incorporated into the resulting embryo, although they are critical for sperm fertilizing capabilities. Embryonic mitochondria are derived from the oocyte and play a large role in energy production during early embryonic development.xx,xxi Thus, red light therapy may have potential applications in fertility for mitochondrial energy production, as eggs and sperm rely on mitochondria for their energy needs during the reproductive process.

Further, red light therapy has also been shown to increase blood flow to treated tissues, which is believed to be mediated by an increase in nitric oxide (NO) formation.xxii,xxiii Nitric oxide, an effective antioxidant, acts to maintain healthy physiological levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The body requires a certain level of ROS for proper cellular function; however, increased ROS levels cause a state of oxidative stress. Aging is associated with an increase in ROS accompanied by a decrease in antioxidants which counteract negative ROS effects. Oxidative stress has well-documented detrimental impacts on both male and female fertility.xxiv,xxv Hence, in theory, red light therapy may address age-related fertility concerns by improving blood flow and reducing oxidative stress.

Overall, proper oocyte and sperm cell mitochondrial function is imperative for fertility. Given the proposed advantages of red light therapy on the mitochondrial function in other cell types,xxvi, xxvii there is the potential for improvement in fertility with the use of red light therapy. Furthermore, its capacity to reduce oxidative stress, a common issue in age-related fertility concerns, adds another dimension to its potential benefits in this context. While this means that fertility benefits remain plausible via these mechanisms, evidence supporting its use and mechanism of action are still lacking (discussed below).

Red light therapy for male infertility: research evidence

Sperm cells rely heavily upon mitochondrial ATP production for optimal sperm motility and physiological reactions necessary for fertilization.xxviii Some research findings suggest there may be beneficial effects of LED red light on sperm cells.xxix, xxx, xxxi The potential benefits may include increased cell survival and motility.

One of the first studies to investigate laser light exposure, conducted in the early 1980s, suggested human ejaculate exposure to red laser light could stimulate motility in live sperm cells that were previously non-motile; however, no differences in sperm velocity were noted and the effects on reproductive outcomes (i.e. clinical pregnancy or live birth rates) were not investigated in the study.xxxii

A different small study found that red light exposure of frozen-thawed human sperm samples resulted in a significantly increased velocity compared to non-treated sperm. xxxiii While the study observed no significant level of DNA damage induced by red light therapy, there was again no impact of red light therapy on reproductive outcomes.xxxiv

In 2014, researchers from Iran published findings examining the effects of red light therapy on human sperm motility using fresh semen specimens from patients with low sperm motility (called asthenospermia).xxxv The findings showed that sperm cells exposed to a low level laser had increased progressive motilityxxxvi It should be noted that the wavelength of light used in this study was in the infrared range, just outside of the red light range, as described above.

These three studies examining the effects of low light therapy were performed on sperm cells collected from human ejaculate. However, the potential effects of direct exposure of the testes to red light in humans are not well-documented. Data collected from animal studies suggest photobiomodulation therapy impacts sperm quality when applied directly to the testes. Mice with heat-induced azoospermia, or lack of sperm, due to elevated testicular temperatures, underwent testicular IR laser exposure over the course of 21 days.xxxvii Researchers found the mice receiving testicular laser treatment experienced a restoration of sperm cell production and overall healthier testicular tissue in comparison to the non-laser-exposed mice.xxxviii

One very small clinical study in Indonesia examined the effect of direct testicular irradiation in humans. The 20 study participants had each testicle irradiated for four minutes two times per week. for a total of 10 sessions.xxxix Laser treatment in men with azoospermia (absence of sperm in the ejaculate) did not lead to an improvement in sperm count. However, men with oligospermia (low sperm count) had an average 2.7-fold and 3.6-fold increase in sperm counts.xl No adverse effects were reported by any of the 20 men included in the study.xli There is a lack of good quality and validated published evidence related to using red light therapy directly on the testes, and further studies are needed.xlii

Overall, there is little published evidence supporting the use of red light therapy for male fertility in humans. Furthermore, in the published studies showing potential improvement to sperm, the impact on reproductive outcomes, such as live birth rates, has not been studied.

Red light therapy for female infertility: research evidence

It is well documented that fertility decreases with age in women, especially as they approach their mid 30s.xliii,xliv One major factor driving this decline in female fertility associated with age is decreased oocyte quality.xlv The occurrence of aneuploidy (having too few or too many copies of a chromosome), becomes more common as women get older, likely due to the impact of age on chromosomes.

In addition, aging oocytes contain aged mitochondria which may not be as efficient at energy production.xlvi,xlvii,xlviii,xlix Mitochondria are the energy organelles inside of cells. Oocytes contain a very high number of mitochondria which provide large amounts of energy to the oocyte during maturation and throughout early embryonic development.l,li,lii,liii Therefore, as red light therapy is believed to improve cellular mitochondrial function, there is the potential for red light therapy to also improve mitochondrial metabolism in aging oocytes. However, more research is needed to verify this experimentally and clinically.

There are very few research studies that have thoroughly characterized the effect of red light therapy on female fertility. In 2010, a Japanese research group reported a clinical study where the effect of an IR laser (830 nm) was examined in female patients seeking fertility treatment.liv Although they observed that the women who became pregnant had received more IR therapy sessions than those that did not become pregnant (3.1 vs 2.6 sessions),lv there are various limitations to the study that prevent the results from being generalizable. For example, most of the patients were over 40 years old, with over half >43yr in the non-pregnant group, and the pregnancy rate was very low (16.5 percent, 97/491).lvi Additionally, details of the specific type(s) of infertility treatment patients received was not described. We included the study here to demonstrate the paucity of quality research in this area. Because of the study limitations, conclusions on any fertility impact cannot be made from these results.

Another study, from Iran, assessed the ability of direct red light exposure to help improve the maturation of immature oocytes retrieved from 36 women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) following ovarian stimulation for IVF.lvii The oocytes exposed to red light (640nm) had a significantly higher rate of in vitro maturation (IVM, 111/155 reached MII mature stage) compared to the non-exposed control oocytes (78/159 reached MII stage).lviii This was also accompanied by a decline in reactive oxygen species (ROS) compared to controls. The impact on fertilization rates or IVF outcomes were not investigated in the study.lix

Animal models have also been utilized to study the effects of photobiomodulation on female fertility. Using a rat model of PCOS, treatment with red light therapy was found to decrease the number of ovarian cysts while increasing ovulation and follicle number, compared to a PCOS control group.lx The findings have not yet been validated in humans.

Another frequent cause of female infertility, poor endometrial receptivity, is a result of endometrial conditions inconducive to embryo implantation. One factor that may contribute to poor implantation is inadequate endometrial thickness.lxi As red light laser therapy is known to enhance cell proliferation (cell division), it is being examined as a therapy method to increase endometrial thickness (still in early experimental stages). Following the exposure of endometrial cell samples to a red laser of 635 nm in vitro (in the lab), researchers found the red light-exposed cells had significantly increased in cell number and surface area in comparison to control cells.lxii In addition, the red light therapy treatment increased the expression of genes known to be important to endometrial receptivity. It was also noted that multiple exposure periods further improve cell proliferation. Overall, this study suggests benefits for endometrial cells following direct exposure to red light therapy. However, this cannot yet be generalized in vivo (in living individuals) until more research is completed; the effects of red light therapy on endometrial function and fertility when applied directly on the pelvic region have not been thoroughly investigated.

There are currently no randomized control trials examining the use of red light therapy directly on the body for the improvement of fertility in either males or females. Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard in research when determining the effectiveness of potential treatment. Analysis of the current research suggests that the use of red light therapy may potentially enhance the quality of both oocytes and sperm cells and increase endometrial cell receptivity in a laboratory setting, but there remains a lack of research supporting its actual clinical effectiveness.

Is red light therapy safe? Side effects of red light therapy

Red light therapy is an emerging technology in the field of fertility, and additional research is required to fully examine the safety, effectiveness, and both short-term and long-term effects.

Studies have investigated the safety of red light therapy for the treatment of other medical issues, such as musculoskeletal and dermatological conditions.lxiii,lxiv Visible light therapies, such as red light therapy, do not utilize harmful, cancer-causing light rays such as UV. Further, there is no clinical trial data linking red light therapy with any significant negative side effects.lxv However, it is worth noting that this has not been fully investigated directly in female pelvic structures or male genitalia.

While many devices are available on the market for at-home use, buyers should be aware of red light therapy devices marketed as “FDA approved,” as the FDA does not approve these devices. Consumers, especially males, should be cautious of red light therapy devices that produce heat. It is critical for sperm production that testicular temperature remains approximately two to three degrees Celsius below body temperature; therefore, heat emitting red light devices may have a negative impact on spermatogenesis and overall male fertility.lxvi

It has been suggested that one potential unwanted side effect of red light therapy is DNA damage due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are generated in the process. For example, 630 nm laser light stimulation has been shown to increase production of ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in mouse sperm.lxvii At high levels, reactive oxygen species can damage the DNA inside a cell and thus researchers have suggested that this should be investigated further. One 2017 study showed that oxidative damage was not increased in sperm exposed to 633 nm red laser light in order to improve sperm motility. The study analyzed oxidative damage in the sperm DNA and found no evidence that irradiation caused DNA damage.lxviii

Similarly, researchers reported in 2023 that red light treatment of human PCOS oocytes undergoing in vitro maturation experienced a decrease in ROS levels, accompanied by a decrease in cell-degradation related gene expression.lxix

A study in Egypt using cultured endometrial cells examined potential negative effects of sustained laser exposure.lxx Findings showed that the higher laser dosage and increased laser exposure time (20 minutes vs. 10 minutes) resulted in thermal damage to endometrial cells. While this study was conducted in a lab using cultured endometrial cells, findings from this experiment further emphasize the importance of caution of both laser strength and exposure time when considering red light therapy.lxxi

Given the variability of study results to date, individuals seeking red light therapy for fertility benefits should remain cautious, as various companies are marketing red light therapy and associated devices without strong peer-reviewed evidence to back them up.

Timing and logistics

Limited fertility providers may offer red light therapy add-ons for fertility treatment, but it is not common and lacks evidence of effectiveness (discussed above). It may also be offered by medical spas and at acupuncture clinics. Medical LED light therapy devices are also available for purchase for at-home use, though there is very little evidence as to their effectiveness.

A specific type of red light therapy, called laser acupuncture, can be offered the day of embryo transfer.lxxii This therapy includes the use of a small pen-like device that emits a low-level red light laser. Treatment can be focused on points often targeted with regular acupuncture such as the ears, abdomen, arms, legs, and top of the head for approximately half a minute per area.lxxiii, lxxiv This treatment is painless and can be offered before the transfer, after the transfer, or both. The goal of laser acupuncture is to increase blood flow to the uterus to increase implantation success.lxxv

There are larger red light (and near red light) emitting devices which are available for focusing on the abdominal/pelvic area to focus treatment on the uterus and/or ovaries. Therapy sessions are usually recommended for a duration of 20 minutes.lxxvi,lxxvii Because red light therapy is believed to impact cellular activity by increasing mitochondrial production of ATP, there is theoretical potential for red light therapy to improve egg quality which would increase fertility. Additionally, women may also potentially benefit from red light therapy by promoting blood flow to support embryo implantation.lxxviii, lxxix

Red light therapy for male fertility may be offered using similar devices at acupuncture clinics, which directs red light to the cells located in the testicle which stimulate sperm production, known as Sertoli cells. For men seeking improved sperm-related benefits, red light therapy sessions could theoretically be beneficial up to three months in advance for couples seeking assisted reproductive technologies including IUI or IVF. While men produce sperm every day, the period it takes to produce mature, motile sperm from immature spermatogonia is approximately 3 months.lxxx

Overall, the lack of substantial clinical data remains a concern in research for this type of therapy, and its effectiveness for enhancing egg quality and male fertility lacks robust peer-reviewed research. Furthermore, recommendations from medical societies and organizations have also not endorsed the use of red light therapy.

Conclusion

In summary, red light therapy may hold promise in enhancing male and female fertility by potentially improving mitochondrial energy production, blood flow, and reducing oxidative stress. However, the available peer-reviewed research in this area is minimal. While preliminary research is encouraging, further clinical studies are necessary to confirm its theoretical effectiveness. Although there are no studies indicating negative side effects of red light therapy, additional studies are required to address any potential risks and to ensure overall general safety. Patients reading about red light therapy on blogs, social media, or other non-scientific sources should be weary of any claims that red light therapy for fertility is supported by clinical research. Given the lack of evidence, and lack of support from medical societies, individuals considering red light therapy for fertility should consult with medical professionals before using red light therapy during their fertility journey.

i International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) (2020). Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDS): Implications for Safety. Health physics, 118(5), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001259

ii International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) (2020). Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDS): Implications for Safety. Health physics, 118(5), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001259

iii International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) (2020). Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDS): Implications for Safety. Health physics, 118(5), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001259

iv Glass, G. E. (2021). Photobiomodulation: A review of the molecular evidence for low level light therapy. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 74(5), 1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2020.12.059

v Karu T. (1989). Photobiology of low-power laser effects. Health physics, 56(5), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-198905000-00015

vi Karu, T. I. (2008). Mitochondrial Signaling in Mammalian Cells Activated by Red and Near-IR Radiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 84(5), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00394.x

vii Karu, T. I. (2008). Mitochondrial Signaling in Mammalian Cells Activated by Red and Near-IR Radiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 84(5), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00394.x

viii Karu, T. I. (1989). Photobiology of Low-power Laser Effects. Health Physics, 56(5), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-198905000-00015

ix Lehtinen, K., Nokia, M. S., & Takala, H. (2022). Red Light Optogenetics in Neuroscience. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2021.778900

x Huang, Y., Chen, A., Carroll, J. D., & Hamblin, M. R. (2009). Biphasic Dose Response in Low Level Light Therapy. Dose-Response, 7(4), dose-response.0. https://doi.org/10.2203/dose-response.09-027.hamblin

xi Desmet, K. D., et al. (2006). Clinical and experimental applications of NIR-LED photobiomodulation. Photomedicine and laser surgery, 24(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2006.24.121

xii Keszler, Á., Lindemer, B., Weihrauch, D., Jones, D. W., Hogg, N., & Lohr, N. L. (2017). Red/near infrared light stimulates release of an endothelium dependent vasodilator and rescues vascular dysfunction in a diabetes model. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 113, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.012

xiii DeSmet, K. D., Paz, D., Corry, J. J., Eells, J. T., Margaret T.T. Wong‐Riley, Henry, M. M., Buchmann, E., Connelly, M. P., Dovi, J. V., Liang, H., Henshel, D. S., Yeager, R. L., Millsap, D. S., Lim, J., Gould, L., Das, R., Jett, M., Hodgson, B. D., Margolis, D., & Whelan, H. T. (2006). Clinical and Experimental Applications of NIR-LED Photobiomodulation. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 24(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2006.24.121

xiv Keszler, Á., Lindemer, B., Weihrauch, D., Jones, D. W., Hogg, N., & Lohr, N. L. (2017). Red/near infrared light stimulates release of an endothelium dependent vasodilator and rescues vascular dysfunction in a diabetes model. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 113, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.012

xv Karu, T. I. (2008). Mitochondrial Signaling in Mammalian Cells Activated by Red and Near-IR Radiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 84(5), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00394.x

xvi Lajos Pikó, & Matsumoto, L. (1976). Number of mitochondria and some properties of mitochondrial DNA in the mouse egg. Developmental Biology, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-1606(76)90253-0

xvii Adhikari, D., et al. (2022). Oocyte mitochondria—key regulators of oocyte function and potential therapeutic targets for improving fertility. Biology of Reproduction, 106(2), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioac024

xviii Friderun Ankel‐Simons, & Cummins, J. (1996). Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(24), 13859–13863.

xvix Friderun Ankel‐Simons, & Cummins, J. (1996). Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(24), 13859–13863. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.24.13859

xx Adhikari, D., et al. (2022). Oocyte mitochondria—key regulators of oocyte function and potential therapeutic targets for improving fertility. Biology of Reproduction, 106(2), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioac024

xxi Friderun Ankel‐Simons, & Cummins, J. (1996). Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(24), 13859–13863. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.24.13859

xxii Karu, T. I., et al. (2005). Cellular effects of low power laser therapy can be mediated by nitric oxide. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, 36(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.20148

xxiii Stepanov, Y. V., et al. (2022). Red and near infrared light-stimulated angiogenesis mediated via Ca2+ influx, VEGF production and NO synthesis in endothelial cells in macrophage or malignant environments. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B-Biology, 227, 112388–112388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2022.112388

xxiv Ruder, E. H., et al. (2009). Impact of oxidative stress on female fertility. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 21(3), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1097/gco.0b013e32832924ba

xxv Bisht, S. F., et al. (2017). Oxidative stress and male infertility. Nature Reviews Urology, 14(8), 470–485. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.69

xxvi Hamblin, M. R. (2016). Shining light on the head: Photobiomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clinical, 6, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbacli.2016.09.002

xxvii Karu, T. I. (2008). Mitochondrial Signaling in Mammalian Cells Activated by Red and Near-IR Radiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 84(5), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00394.x

xxviii Hirata, S., et al. (2002). Review Spermatozoon and mitochondrial DNA Spermatozoon and mitochondrial DNA. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 1, 41–47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5904680/pdf/RMB2-1-41.pdf

xxix Moskvin, S. V., & Apolikhin, O. I. (2018). Effectiveness of low level laser therapy for treating male infertility. BioMedicine, 8(2), 7. https://doi.org/10.1051/bmdcn/2018080207

xxx Preece, D., et al. (2017). Red light improves spermatozoa motility and does not induce oxidative DNA damage. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46480

xxxi Eghbaldoost, A., et al. (2023). Therapeutic Effects of Low-Level Laser on Male Infertility: A Systematic Review. Journal of Lasers in Medical Sciences, 14, e36–e36. https://doi.org/10.34172/jlms.2023.36

xxxii Sato, H., M., et al. (2009). The Effects of Laser Light on Sperm Motility and Velocity in vitro. Andrologia, 16(1), 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0272.1984.tb00229.x

xxxiii Preece, D., et al. (2017). Red light improves spermatozoa motility and does not induce oxidative DNA damage. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46480

xxxiv Preece, D., et al. (2017). Red light improves spermatozoa motility and does not induce oxidative DNA damage. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46480

xxxv Yazdi, R. S., et al. (2013). Effect of 830-nm diode laser irradiation on human sperm motility. Lasers in Medical Science, 29(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-013-1276-7

xxxvi Yazdi, R. S., et al. (2013). Effect of 830-nm diode laser irradiation on human sperm motility. Lasers in Medical Science, 29(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-013-1276-7

xxxvi Ziaeipour, S., et al. (2023). Photobiomodulation therapy reverses spermatogenesis arrest in hyperthermia-induced azoospermia mouse model. Lasers in Medical Science, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-023-03780-8

xxxvii Ziaeipour, S., et al. (2023). Photobiomodulation therapy reverses spermatogenesis arrest in hyperthermia-induced azoospermia mouse model. Lasers in Medical Science, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-023-03780-8

xxxix Hasan, P., et al. (2004). THE POSSIBLE APPLICATION OF LOW REACTIVE-LEVEL LASER THERAPY (LLLT) IN THE TREATMENT OF MALE INFERTILITY: A preliminary report. LASER THERAPY, 14(0_Pilot_Issue_2), 0_65–0_66. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.14.0_65

xl Hasan, P., et al. (2004). THE POSSIBLE APPLICATION OF LOW REACTIVE-LEVEL LASER THERAPY (LLLT) IN THE TREATMENT OF MALE INFERTILITY: A preliminary report. LASER THERAPY, 14(0_Pilot_Issue_2), 0_65–0_66. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.14.0_65

xli Hasan, P., et al. (2004). THE POSSIBLE APPLICATION OF LOW REACTIVE-LEVEL LASER THERAPY (LLLT) IN THE TREATMENT OF MALE INFERTILITY: A preliminary report. LASER THERAPY, 14(0_Pilot_Issue_2), 0_65–0_66. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.14.0_65

xlii Effectiveness of low level laser therapy for treating male infertility | Semantic Scholar. (2018). Semanticscholar.org; https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/ff35581212d9e9db35d5451056a741e472b9d45f

xliii Female age-related fertility decline. (2014). Fertility and Sterility, 101(3), 633–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.032

xliv Reza, A., et al. (2021). Oocyte quality and aging. JBRA Assisted Reproduction. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210026

xlv Reza, A., et al. (2021). Oocyte quality and aging. JBRA Assisted Reproduction. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210026

xlvi Kitagawa, T., Suganuma, N., Nawa, A., Fumitaka Kikkawa, Tanaka, M., Ozawa, T., & Tsutsumi, Y. (1993). Rapid Accumulation of Deleted Mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic Acid in Postmenopausal Ovaries. Biology of Reproduction, 49(4), 730–736. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod49.4.730

xlvii Robert P.S. Jansen, & K de Boer. (1998). The bottleneck: mitochondrial imperatives in oogenesis and ovarian follicular fate. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 145(1-2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00173-7

xlviii Wang L, Tang J, Wang L, et al. Oxidative stress in oocyte aging and female reproduction. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(12):7966-7983. doi:10.1002/jcp.30468

xlix May-Panloup P, Boucret L, Chao de la Barca JM, et al. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(6):725-743. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmw028

l Female age-related fertility decline. (2014). Fertility and Sterility, 101(3), 633–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.032

li Adhikari, D., et al. (2022). Oocyte mitochondria—key regulators of oocyte function and potential therapeutic targets for improving fertility. Biology of Reproduction, 106(2), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioac024

lii Friderun Ankel‐Simons, & Cummins, J. (1996). Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(24), 13859–13863. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.24.13859

liii Lajos Pikó, & Matsumoto, L. (1976). Number of mitochondria and some properties of mitochondrial DNA in the mouse egg. Developmental Biology, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-1606(76)90253-0

liv Taniguchi, Y., Ohshiro, T., Ohshiro, T., & Sasaki, K. (2010). ANALYSIS OF THE CURATIVE EFFECT OF GaAlAs DIODE LASER THERAPY IN FEMALE INFERTILITY. LASER THERAPY, 19(4), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.19.257

lv Taniguchi, Y., Ohshiro, T., Ohshiro, T., & Sasaki, K. (2010). ANALYSIS OF THE CURATIVE EFFECT OF GaAlAs DIODE LASER THERAPY IN FEMALE INFERTILITY. LASER THERAPY, 19(4), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.19.257

lvi Taniguchi, Y., Ohshiro, T., Ohshiro, T., & Sasaki, K. (2010). ANALYSIS OF THE CURATIVE EFFECT OF GaAlAs DIODE LASER THERAPY IN FEMALE INFERTILITY. LASER THERAPY, 19(4), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.19.257

lvii Sahraeian, S., et al. (2023). Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Cord Blood Plasma and Photobiomodulation Therapy Down-Regulated Caspase 3, LC3 and Beclin 1 Markers in the PCOS Oocyte: An In Vitro Study. Journal of lasers in medical sciences, 14, e23. https://doi.org/10.34172/jlms.2023.23

lviii Sahraeian, S., et al. (2023). Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Cord Blood Plasma and Photobiomodulation Therapy Down-Regulated Caspase 3, LC3 and Beclin 1 Markers in the PCOS Oocyte: An In Vitro Study. Journal of lasers in medical sciences, 14, e23. https://doi.org/10.34172/jlms.2023.23

lix Sahraeian, S., et al. (2023). Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Cord Blood Plasma and Photobiomodulation Therapy Down-Regulated Caspase 3, LC3 and Beclin 1 Markers in the PCOS Oocyte: An In Vitro Study. Journal of lasers in medical sciences, 14, e23. https://doi.org/10.34172/jlms.2023.23

lx Eduardo, A. D., et al. (2019). Photobiomodulation can improve ovarian activity in polycystic ovary syndrome-induced rats. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B-Biology, 194, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.03.006

lxi Richter, K. S., et al. (2007). Relationship between endometrial thickness and embryo implantation, based on 1,294 cycles of in vitro fertilization with transfer of two blastocyst-stage embryos. Fertility and Sterility, 87(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.064

lxii El, A., et al. (2018). Has the time come to include low-level laser photobiomodulation as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of impaired endometrial receptivity? Lasers in Medical Science, 33(5), 1105–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2476-y

lxiii Glass G. E. (2023). Photobiomodulation: A Systematic Review of the Oncologic Safety of Low-Level Light Therapy for Aesthetic Skin Rejuvenation. Aesthetic surgery journal, 43(5), NP357–NP371. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad018

lxiv Ferraz, M., et al. (2022). Low-intensity LASER and LED (photobiomodulation therapy) for pain control of the most common musculoskeletal conditions. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 58(2). https://doi.org/10.23736/s1973-9087.21.07236-1

lxv Glass, G. E. (2023). Photobiomodulation: A Systematic Review of the Oncologic Safety of Low-Level Light Therapy for Aesthetic Skin Rejuvenation. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 43(5), NP357–NP371. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad018

lxvi Wang, C., et al. (1997). Effect of increased scrotal temperature on sperm production in normal men. Fertility and Sterility, 68(2), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81525-7

lxvii Cohen, N., et al. (1998). Light irradiation of mouse spermatozoa: stimulation of in vitro fertilization and calcium signals. Photochemistry and photobiology, 68(3), 407–413.

lxviii Preece, D., et al. (2017). Red light improves spermatozoa motility and does not induce oxidative DNA damage. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46480

lxix Sahraeian, S., et al. (2023). Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Cord Blood Plasma and Photobiomodulation Therapy Down-Regulated Caspase 3, LC3 and Beclin 1 Markers in the PCOS Oocyte: An In Vitro Study. Journal of lasers in medical sciences, 14, e23. https://doi.org/10.34172/jlms.2023.23

lxx El, A., et al. (2018). Has the time come to include low-level laser photobiomodulation as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of impaired endometrial receptivity? Lasers in Medical Science, 33(5), 1105–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2476-y

lxxi El, A., et al. (2018). Has the time come to include low-level laser photobiomodulation as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of impaired endometrial receptivity? Lasers in Medical Science, 33(5), 1105–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2476-y

lxxii Morin, S. J., et al. (2017). Laser acupuncture before and after embryo transfer improves in vitro fertilization outcomes: A four-armed randomized controlled trial. Medical Acupuncture, 29(2), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2017.1218

lxxiii Fratterelli, J. L., et al. (2008). Laser acupuncture before and after embryo transfer improves ART delivery rates: results of a prospective randomized double-blinded placebo controlled five-armed trial involving 1000 patients. Fertility and Sterility, 90, S105–S105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.1252

lxxiv Morin, S. J., et al. (2017). Laser acupuncture before and after embryo transfer improves in vitro fertilization outcomes: A four-armed randomized controlled trial. Medical Acupuncture, 29(2), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2017.1218

lxxv Morin, S. J., et al. (2017). Laser acupuncture before and after embryo transfer improves in vitro fertilization outcomes: A four-armed randomized controlled trial. Medical Acupuncture, 29(2), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2017.1218

lxxvi Taniguchi, Y., et al. (2010). Analysis of the curative effect of GaAlAs diode laser therapy in female infertility. Laser Therapy, 19(4), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.5978/islsm.19.257

lxxvii Phypers, R. (2022, October). Best light for fertility - red and infrared light therapy. Laser Medicine London. https://www.lasermedicine.co.uk/best-light-for-fertility/

lxxviii Karu, T. I., et al. (2005). Cellular effects of low power laser therapy can be mediated by nitric oxide. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, 36(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.20148

lxxix Keszler, Á.,et al. (2017). Red/near infrared light stimulates release of an endothelium dependent vasodilator and rescues vascular dysfunction in a diabetes model. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 113, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.012https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.012

lxxx Griswold M. D. (2016). Spermatogenesis: The Commitment to Meiosis. Physiological reviews, 96(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00013.2015